“Everything that ever happened in the past.”

or

“A field of study and a tool-kit of methods, aimed at analyzing, testing hypotheses about, and conveying to an audience of readers or viewers a coherent, fact-based argument about why those things happened.”

Well, which is it? Trick question! Of course, History’s both. But the distinction is important. Most people who decide to study History as a college subject are drawn to it because they’re fascinated by the former. That may be because they had that teacher, who had the gift of inspiring a lasting fascination. It may be because of their own family’s or community’s history, or visiting places that left an enduring impression. It may be simply because they were that kid, who wanted to read books or watch videos about History when their friends wanted to do something else.

But progressing through a college career as History majors means while studying the content – the “everything that happened” – stays integral to every course, we progressively intensify our drilling of the process – “analyzing, testing, and conveying”. We guide students to find and interrogate their sources, to master the prevailing literature regarding what historians have said about a particular topic (the historiography), to ask formal testable questions, and – above all – to write analytically. Finding and assessing the quality and potential of information – nowadays often accessed digitally (with another set of skills to master), and with a new batch of critical questions to ask about the value of online materials – are as important as putting the results together in a compelling, logical, exposition.

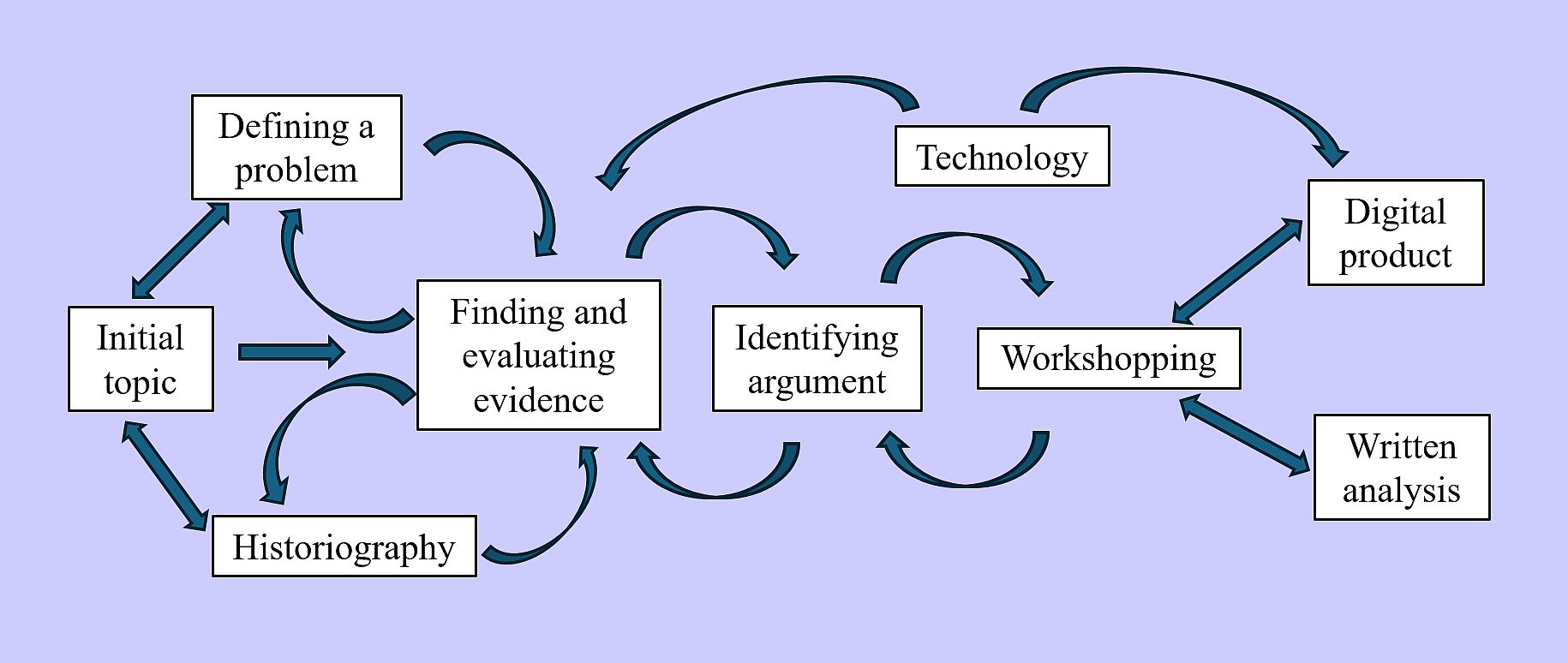

The culmination of the History major in our department is a senior thesis, a written product of a primary-source-based research project, typically 30-40 pages long. (In preparation for this they do two rounds of smaller-scale projects during Junior Seminar, which one of our recent alumni called “boot camp for History majors”, which pleased us all.) Students write their theses in the fall semester of their senior year, but have to begin work on narrowing down to topics and identifying materials months ahead of that. They work through their projects in small seminar groups, with a lot of peer review and critiquing each other’s work. The emphasis is upon specific stages of the project, from topic to literature review to source collation to research proposal, outlining, and multiple drafts. In all this we aspire to make the experience a true reflection of the iterative research process.

Though some historians might feel a pang of discomfiture at the term, these are transferable skills. And though relatively few History majors end up in careers very directly related to the content of the subject (see preceding article), virtually every sector of the job market they end up populating values those transferable skills, as they’re rarer than one might hope. Scrutinize any recent discussion of what firms are looking for, and grasp the similarities to the historian’s craft: communication (written and verbal), critical thinking and analytical reasoning, project planning, collaborative workmodes, and broad cultural awareness.

Our seniors who come out the other end of this process realize how far they’ve been accompanied. Gabriel Toto (class of 2024) says: “My senior thesis seminar was a perfect culmination of studying history at CUA. Through rigorous research, and honing of my writing skills, I completed a near-40-page paper. This was a daunting feat I would not have thought possible my freshman year. But, through three years developing my skills in studying history, I was able to write a thesis I was proud of, harnessing all that I had learned while studying history at CUA.”

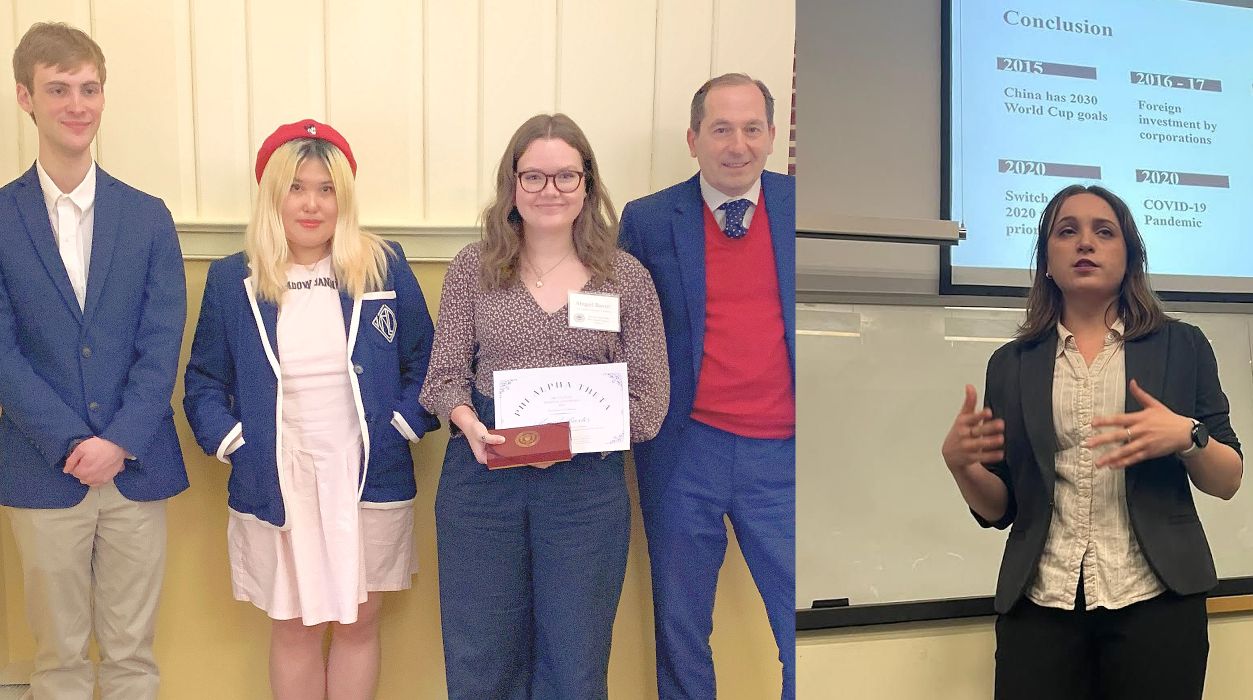

(l-r) Michael Halick, Matilda Jingwen Zhao, and Abigail Baxter, with Professor Árpád von Klimó (Director of Undergraduate Studies) at the Phi Alpha Theta regional conference 2023 at Washington College (Chestertown, MD); Abigail won the award for the best paper in the category of World (Non-U.S.) History, for her presentation titled “‘She has Butter on Everything, even Toast!’: Britishness, Femininity, and Self-Sacrifice during the Second World War”. Chloe Masaitis presenting “The PRC’s Internazionale Milano: Chinese Business Dynamics in International Football Investments” at Catholic University’s Research Day, 2024.

Our students regularly parlay their Junior Seminar and Senior Thesis projects into presentations: every spring we celebrate our thesis-writers and have them give capsule summaries of their work, at the annual University Research Day up to a dozen History majors give lecture-style adresses or poster sessions, each year we take students to the regional conference of Phi Alpha Theta (the national honors society for History) to give papers, and most issues of Inventio (Catholic University’s undergraduate research journal) include articles by our students.

“Everything that happened” will always encapsulate the fascination in our subject that we share with our students. “Analyzing, testing, and conveying” is at the heart of what we all do.