There were also culture clashes with the non-veteran students on campus: the university’s bookstore was “not used to students being able to buy all their books at once, as veterans were thanks to the Veterans’ Administration,” and as Harry sat on the lawn outside McMahon to inspect all the textbooks he’d just bought he heard a non-veteran passing by, saying she was going to transfer to another college next semester. “She said, ‘I can't stand this place, everyone studies!’”

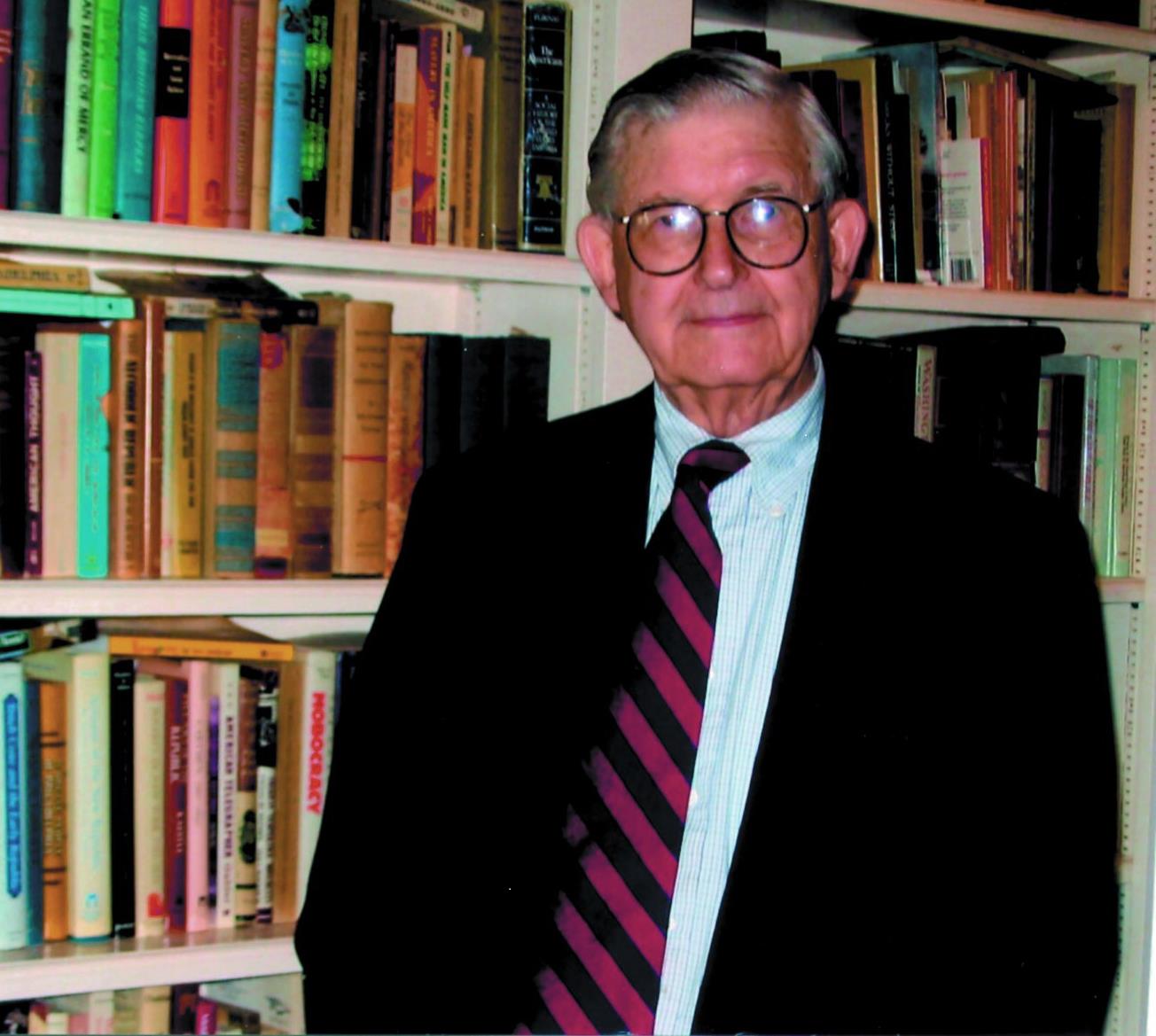

Harry went on to a doctorate at Penn and a distinguished career as a historian, first at the Library of Congress, then the Department of State, and as a fulltime member of CUA’s History Department faculty from 1964 until 1969, when he became associate curator of naval history at the Smithsonian. He continued to teach part-time at CUA until 1997, and offered highly popular courses in World War II and U.S. diplomatic history in the basement of Gibbons Hall – where the History Department was then located – just a couple of floors down from where he’d lived as an undergraduate.

Harry is the author or editor of numerous books, including Roosevelt and Churchill: Their Secret Wartime Correspondence (1975) and the prize-winning A History of Medicine in the Early U.S. Navy (1995). He has received awards from the North American Society for Oceanic History, the U.S.S. Constitution Museum, and the Naval Historical Foundation. He retains vivid memories of his undergraduate history instructors and stayed in touch with many of them: for instance, Edward Lilly in American history, Manuel Cardozo in Latin American history, and Monsignor John Tracy Ellis in church history. But a particular memory is of Sister Marie Carolyn Klinkhammer, who taught a survey course in European History, required for Arts and Sciences students, in the auditorium of McMahon. “She stood at a lectern on stage and lectured without notes for the whole period. I thought that I kept up with the course and the readings pretty well, but was shocked when I got a grade of C on a early test. Later I encountered Sister Marie on the walkway from McMahon Hall. I said, “Sister, how come I got a C on the quiz?” In a somewhat haughty manner she replied: ‘Mr. Langley! A great many students flunked!’ Enough said.”

One of his vivid teaching memories was a summer school course in American history, taken mostly by nuns and a few priests. “All the nuns were in full habits in those days,” the Washington summer was hot then as now, and the sole means of cooling was a fan so loud nobody could hear. Harry made his opinion of this arrangement known, and the director of summer school “wanted to know who this guy Langley was who was raising all these issues.”